Racism is a public health issue and the recent deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and the incident involving Christian Cooper only reinforce what many within public health have known for some time: racism is a determinant of health. Yet despite this recognition and long-held belief, there remains insufficient practice and research drawing stronger causal evidence regarding the impact and experience of racism on subsequent health and health outcomes. In other words, the acknowledgment without deliberate and continuous action is merely an exercise in sympathy.

To their credit, those working across the public health system, through frameworks such as Healthy People 2020, have sought to prioritize health equity. The challenge, however, is that in defining health equity the field is missing the mark. Healthy People 2020 notes:

Achieving health equity requires valuing everyone equally with focused and ongoing societal efforts to address avoidable inequalities, historical and contemporary injustices, and the elimination of health and health care disparities.

While a noble value proposition, this statement assumes public health practitioners hold shared values, ignoring bias—whether implicit or explicit—and the role it plays in shaping our world view. Further, the statement asks public health practitioners to simply, “value everyone equally,”—which does little to solve the problem. Yes, as a baseline, health equity requires that everyone is valued and is seen as having value, but that can only occur after deep personal work and accountability. It doesn’t come by osmosis; it will not just happen. More importantly, health equity demands a focused pursuit in achieving equity, which recognizes that not everyone should be treated the same.

Accountability and Equity

Racism is intricately woven into the fabric of American culture and is historically entrenched in health. The foundation of traditional public health practice is built on scientific racism and ideas of white supremacy perpetuated by 19th Century scientists of the university community, as well as the medical community. To bring about meaningful change, public health professionals must recognize this and work to acknowledge and confront their privilege and biases. Additionally, public health professionals must take responsibility for naming, understanding, disrupting, and ultimately dismantling the elephant in the room: racism.

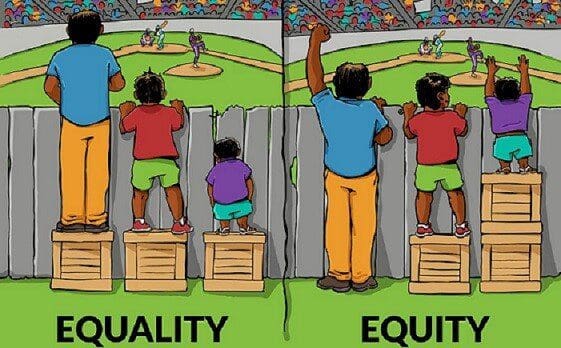

As it relates to equity, the term has, on occasion, been conflated with “equality,” but in practice, equity requires far more effort and consideration. Equitable solutions necessitate an adjustment of approach to account for disproportionate burdens and historic and present injustices. For any organization, institution, or system it is imperative that—at every level—there is a shared understanding of what it means to practice equity. Fundamentally, equity is about fairness. It is the recognition that all people do not start from the same place. An equity approach recognizes that persistent disparities will not be solved without intentionality in how policymakers target opportunities, resources, and supports, or how public health professionals question, research, analyze, and report critical information.

Credit: Interaction Institute for Social Change / Artist: Angus Maguire

People of color, and Black people specifically, have endured and continue to suffer from the impacts of racism, which presents barriers to social and economic participation, resulting in entrenched disadvantage and social exclusion. The health consequences of racism are significant and manifest in poor health outcomes. In an article featured in the American Journal of Public Health, Jennifer Jee-Lyn Garcia, PhD, and Mienah Zulfacar Sharif, MPH state:

The health consequences of living in a racially stratified society are illustrated by a myriad of health outcomes that systematically occur along racial lines, such as disproportionately higher rates of infant mortality, obesity, deaths caused by heart disease and stroke, and an overall shorter life expectancy for Blacks in comparison with Whites. Thus, we argue that racialized health disparities are a consequence of racism, not race, per se. Although both race and racism are relevant to health, typically only race is included as a research question, variable, or topic in most health studies. Race, as it is conventionally conceptualized and operationalized in public health research, is not an adequate proxy measure for racism.

Similarly, as Dr. Nancy Krieger, an epidemiologist, and professor of social epidemiology at the Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health explained:

A person is not one day African American, another day born low birth weight, another day raised in a home bearing remnants of lead paint, another day subjected to racial discrimination at work (and in a job that does not provide health insurance), and still another day living in a racially segregated neighborhood without a supermarket but with many fast-food restaurants. The body does not neatly partition these experiences—all of which may serve to increase risk of uncontrolled hypertension.

Practicing Public Health Equity in the Real World

The uncomfortable truth is that health equity is unachievable unless and until we address and tackle racism. Those within and around the public health system must commit to the following actions:

Speaking Truth to Power

The insidious effects of racism permeate our systems, policies, and institutions. As champions of public health, the field must commit to calling racism by its name. There is power in words and refusing to name racism allows us to deny or dismiss its impact, or worse, pretend we are talking about something else entirely. We owe it to ourselves and the betterment of the field to speak truth to power, even and especially when the truth is painful, uncomfortable, or embarrassing.

Ongoing Cultural Competence

Because myriad factors influence health communication to include language, customs, values, and beliefs, we must educate ourselves so that we may engage with others respectfully, sensitively, and competently. Ongoing cultural competence carries with it enormous benefits to include supporting positive health outcomes and helping the field to achieve accuracy in health research and interventions. For this reason, health practitioners, departments, organizations, and foundations should embrace mandatory implicit bias training coupled with continuing education courses focused on cultural competency and cultural respect.

Redefining Equity

“When you’re accustomed to privilege, equality/equity feels like oppression.”

As mentioned previously, equity is about fairness. “Valuing everyone equally,” as Healthy People 2020 suggests, still results in many inequities. This is because simply valuing and treating people the same fails to recognize that in practice, people will need different supports, services, resources, and solutions to achieve success and optimal well-being. Public health cannot apply a one-size-fits-all solution to complex problems, and some city leaders understand this and are doing the work to improve.

While we applaud those leaders committed to this work, they should continue their current course and still do even more. More must be done to understand the unique challenges and barriers faced by individuals and across different populations. We will not realize equal outcomes but the goal should be to ensure that every person has an equal opportunity to live their healthiest, best life. This can only be accomplished through intentional interventions that meet people exactly where they are.

Filling the Gaps

Where knowledge gaps exist about the impact of racism on health and well-being, public health professionals must fill them. This means understanding, researching, analyzing, and documenting racism as a problem and its consequences. Further, it requires the field to identify practical and innovative solutions to tackle this complex problem. Additionally, public health professionals should be critical when evaluating the work of the field, to uncover and challenge implicit or explicit bias.

Creating Opportunities

Achieving the goal of eliminating disparities in health cannot be accomplished without a diverse group of health professionals. Simply put, foundations, organizations, institutions, and departments must recruit, hire, and promote people of color. These entities should regularly evaluate their recruitment and hiring practices and commit to elevating the voices of people of color across their respective enterprises and specifically in leadership roles. This effort however is only a preliminary step. Having a seat at the table is not enough if those occupying certain positions do not feel safe, valued, seen, or heard. We must all work to establish a culture of belonging in our respective workplaces—the actualization of fully accepting people for their unique traits and embracing and encouraging the richness of their differences. In creating opportunities for people of color we ensure their lived experiences inform the collective work, unlock innovation, and challenge conventional wisdom.

Advocating for Federal, State, and Local Policy

Finally, the work of the public health field extends only so far, and then it is up to our elected officials and policymakers to codify change. Public health professionals play a critical role in helping lawmakers understand critical health issues. To this end, more must be done to continuously educate policymakers and the public and then advocate, at all levels, for equity-centered policies.

Policy is one of public health’s greatest tools to influence positive health outcomes and effect generational change. At CityHealth, we work to reshape communities through evidence-based policy change, to ensure that one’s racial identity is not a predictor of their educational, economic, health, or other outcomes. But policy alone is not a panacea.

Disrupting systemic power imbalances and dismantling racism is lifetime work. It requires a daily commitment to deliberate action. It commands fearlessness and above all, personal and professional accountability. This work is our moral imperative if we are to ensure that everyone, in every state, county, and city is afforded the opportunities and resources necessary to live their best, healthiest lives.